Aquaculture Nutrition and Diet Management

Energy Metabolism:

In general, nutritional compounds can be divided into energy-efficient and non-energy-consuming nutrients. Proteins, fats and carbohydrates are in the energy group and vitamins and minerals are in the non-energy group.

These compounds have numerous physiological and biochemical functions and are important in determining the efficiency of food. The first function of food in fish and crustaceans such as shrimp is to supply the energy needed to maintain survival, growth and reproduction.

The benefits of using energy in fish and aquatic crustaceans are that they are primarily cold-blooded animals and do not consume energy to maintain their body temperature against ambient temperatures; and the land requires less energy.

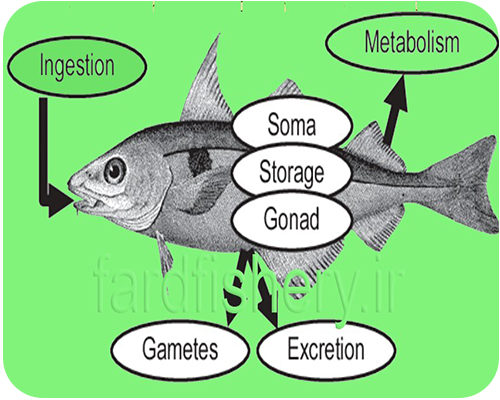

Some of the energy in the feed is consumed partially for growth and metabolic activities necessary, and the rest is discharged either as unhealthy foods or as heat and excretory compounds.

Most of the energy is excreted through the excretion of undigested foods and the least is excreted through ammonia and urine.

Definition of digestible energy:

The portion of food energy that the body is able to digest or absorb, or simply the number derived from the stool energy fraction of total energy, represents digestible energy.

Definition of metabolizable energy:

Includes total energy, minus energy excreted through the stool, urine and gill discharge

In the regulation of aquatic diets, the amount of digestible energy is usually used instead of the amount of metabolizable energy. The digestible energy of nutrients in fish and shrimp is determined using various methods to measure the amount of relative energy consumed and feces. According to aquatic nutritionists, there is no limit to the use of digestible energy in regulating aquatic diets because the energy wasted through the gills and the kidneys is very small compared to wasted through the digestive tract.

What are the factors affecting energy consumption?

1) Fish species: For example, stagnant water species have a lower metabolism rate than oceanic species.

2) Fish size: Generally, as fish size increases, their metabolism speeds down.

3) Nourine or Photoperiod: Darkness reduces energy requirements of some species.

4) Diet composition: If the diet contains high protein and minerals, the metabolism speeds up to prevent the accumulation of toxic waste in the body, so it can be concluded that the metabolism rate in carnivorous species is higher than that of vegetarians.

5) Physiological Activity: Fish have high metabolic activity during the spawning season.

6) Fish Age: In general, the rate of metabolism decreases with age.

7) Water temperature: As the water temperature decreases as the dissolution capacity of oxygen decreases, the metabolism rate in fish increases.

8) Other Environmental Factors: Factors such as water flow rate, chemical composition and water pollution cause stress to the fish that the rate of metabolism will vary depending on these changes.

So far, we have looked at the factors affecting energy requirements in fish or whole aquatic life, the question being what will be the sources of this energy supply?

Aquatic animals, like other animals, derive their energy from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Because fish use low-carb carbohydrates, fatty fish and sometimes protein are the main sources of energy for breeding.

The gross energy of carbohydrates is 4.15 kcal / g. Carp can digest 30 to 90 percent of the carbohydrates in the diet, while carbohydrate digestibility in trout is only 39 percent.

Carbohydrates can be partially used for energy in the diet of trout rather than protein, but the abundance of carbohydrates in this fish’s diet causes high levels of glycogenesis in the liver and liver and kidney fat. So fat and protein are the main sources of energy in the salmon diet.

Important note:

Unfortunately, some trout feed producers are overwhelmingly adding wheat flour to their rations in order to increase feed buoyancy and extrusion, as well as better biodegradation and ultimately better economic justification. At the end of the period or when the fish is consumed, it has no nutritional value and is immediately collected in the pan.